Marking the 50th anniversary of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case that ushered in the era of busing, a new exhibit currently on display on the main floor of the library for Black History Month tells the story of the desegregation of Charlotte public schools. Separate, But Not Equal: Desegregating Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, uses select materials from the library’s manuscript collections to explore local organizations for and against integration, the desegregation of school personnel, and busing.

When Charlotte formed its public school system in 1880, members of the board of school commissioners operated under the principles of Jim Crow laws that mandated racial segregation. In the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation in public spaces as long as the facilities remained equal in quality. In reality, segregated facilities rarely functioned equally and systematically perpetuated racial inequality. African American schools regularly lacked adequate school buildings, and school personnel in predominantly Black schools received less pay than their white colleagues.

In 1954, the historic Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka court case challenged the legality of racially segregated schools. The Supreme Court ruled against the constitutionality of separate but equal educational facilities and rejected racial segregation in schools. The North Carolina legislature hoped to pass legislation to delay integration in the aftermath of the Brown decision. In 1955, The General Assembly passed the Pupil Assignment Act. The act granted local districts control over student assignments and allowed local officials to deny black students who wished to transfer to white schools. After the Supreme Court ordered schools to desegregate “with all deliberate speed” later in the year, the Pearsall Plan was established. The plan amended the Compulsory School Attendance Law to excuse students from attendance requirements if assigned to an integrated school and could not claim any other private or public school option.

Even though it hindered the process of integration, local African American activists used legislation like the 1955 Pupil Assignment Act to fight for desegregated public schools. Kelly Alexander Sr. and his wife Margaret Alexander helped African American parents complete the forms needed to request the reassignment of their children to predominantly white schools. The Charlotte school board only approved five of the forty applications sent to them in 1957. On September 4, 1957, four of the five approved applicants became the first African American students to integrate four formerly all-White Charlotte public schools. Dorothy Counts integrated Harding High School, Delois Huntley integrated Alexander Graham Junior High School, Gus Roberts integrated Central High School, and Girvaud Roberts integrated Piedmont Junior High School. Of the four students, only Gus Roberts graduated from the school that he helped to integrate.

The local board of education continued to maintain unequal school assignment policies after 1957. In 1964, Dr. Darius and Vera Swann requested the assignment of their son, James Swann, to the predominantly white Seversville Elementary School. The school board denied their request like those of countless other African American parents who tried to make use of the Pupil Assignment Act. Seeking to address the discriminatory system, the Swanns and several African American parents launched a suit against the school board in 1964, known as Swann et al. v. Charlotte- Mecklenburg Board of Education. Judge J. Craven ruled in favor of the school board in the 1964 case. However, the Swanns pursued another suit against the board in 1968, a case which proved a success for civil rights lawyer and activist Julius L. Chambers. The 1971 decision in Swann et al. v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Board of Education was the first busing case by the U.S. Supreme Court, establishing busing as a legal technique for school desegregation. Though the busing policy received mixed reactions from the Black and White communities in Charlotte, the desegregation plan did fully integrate local schools for almost three decades.

Sources:

Charles A. McLean Papers, MS0250, UNC Charlotte.

Charlotte City Board of Education Records, MS0001, UNC Charlotte.

Julius Chambers Papers, MS0085, UNC Charlotte.

Kelly M. Alexander, Sr. papers, MS0055, UNC Charlotte.

NC Desegregation Papers, MS0413, UNC Charlotte.

Reginald Hawkins Papers, MS0125, UNC Charlotte.

--Sylvia Marshall

Sylvia Marshall, the curator of Separate But Not Equal, is a graduate research assistant in the public history program.

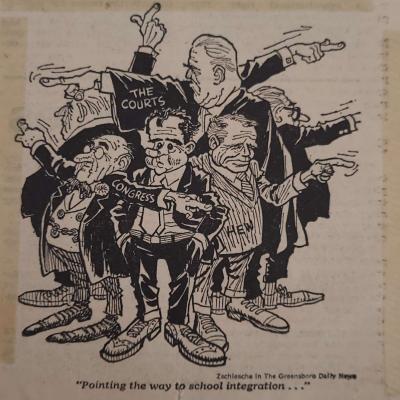

Image: “Pointing the Way to School Integration,” editorial cartoon, Julius Chambers Papers, Atkins Library